These keyboards housed circuit boards with 100 to 120 reed switches, each covered by a key. This Key Tronic keyboard used reed switches to record keystrokes. When the magnetic field gets close enough, it pulls the two filaments together and thus completes a circuit - or, in the case of a key, a keystroke. One of the first computer keyboard designs from the early '70s incorporated reed switches, which work with a magnet and two metal filaments. "How the felt, how reliable it was, what speed could be achieved with a certain design of the switch." "It was a real big deal back then," says Craig Gates, CEO of KeyTronicEMS, as the company is now called. In the late 1970s, companies like Cherry, Key Tronic and the Micro Switch division of Honeywell took off with their own approaches to mimicking the mechanical feel of a typewriter with the circuitry of a computer keyboard.

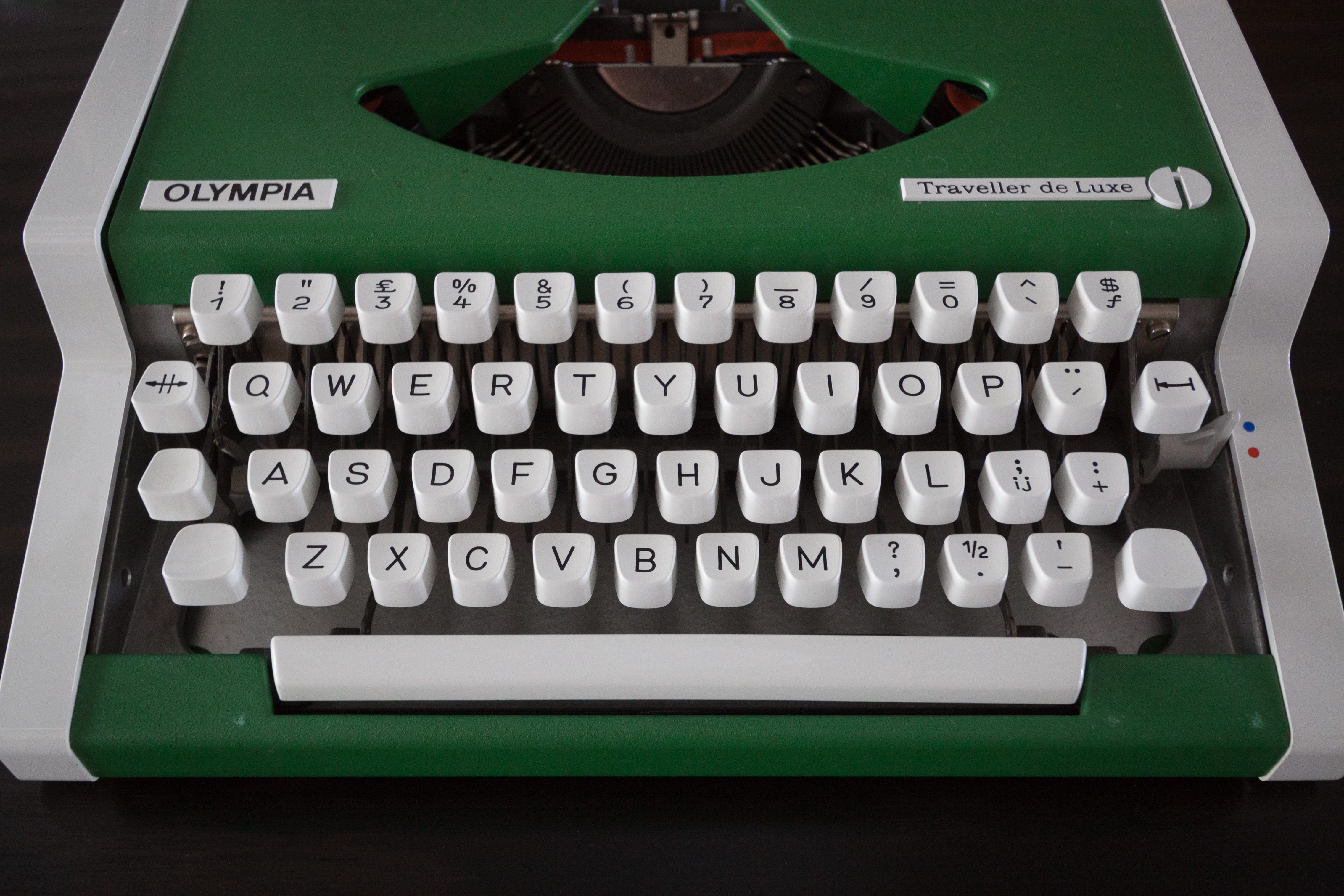

#Typewriter keyboard design Pc

So when the PC hit the scene a decade or two later, the Selectric was largely viewed as the baseline to design keyboards for those newfangled computers you could put in your office or home.

"IBM's probably done more than anyone to find ergonomics that work for everyone," Spicer says. IBM released the first model of its iconic electromechanical typewriter in 1961, a time when being able to type fast and accurately was a highly sought-after skill.ĭag Spicer, senior curator at the Computer History Museum, notes that as the Selectric models rose to prominence, admins grew to love the feel of the keyboard because of IBM's dogged focus on making the ergonomics comfortable. Click to view larger image.Īs far as direct influences on the modern computer keyboard, IBM's Selectric typewriter was one of the biggest. "There was a mechanical advantage required."Įarly computer keyboards mimicked the feel of IBM's classic Selectric typewriter. The shift key was really big because you needed a big surface area to push down and raise the carriage up," says David Hill, vice president of design and user experience at computer manufacturer Lenovo. "The typewriter had all sorts of functions. Some aspects of even these very early keyboards inform a lot about the design today. In 1852 John Jones patented a "mechanical typographer," and 15 years later Christopher Sholes received a patent for a "type-writing machine" - what is usually considered the original typewriter. The first devices we'd recognize as related to modern keyboards date from the 19th century. Contributions to its look, feel and underpinning technologies sometimes draw from preceding models and other times from a far corner of the inventor's universe. The evolution of the keyboard is not a clean timeline. "A lot of the stuff that's emerging as new is rooted in things that have happened in the past - and in some cases the really distant past."īefore we look at where computer keyboards might go in the future, then, let's look at where they've been. "Many of the great discoveries are right under our noses," he says when discussing the future of the keyboard. Click to view larger image.īuxton, now a design guru at Microsoft Research, still closely examines old keyboards for forgotten tricks and technologies that could spawn new ways of thinking about how we enter information into a computer. Maybe eventually we'll connect computers to our neurons, but in the meantime, the simple yet highly functional electromechanical keyboard will be around - and keep improving - for some time.ĭecades after its introduction in the mid-'80s, IBM's classic Model M remains a favorite for keyboard purists. The keyboard has fused with the screen, at least for some computing tasks.īut as anyone who's typed on a virtual keyboard - or yelled at a voice-control app like Siri - can attest, no current text input holds a candle to a traditional computer keyboard when it comes to comfort, speed and accuracy. Inputs and outputs share the same surface. Fast-forward a couple decades - and add myriad researchers and huge corporate R&D budgets - and we have touch-screen keyboards on tablets and smartphones. Why, Buxton asked, couldn't the same principle apply to text on computers - using a single device for both input and output of text rather than using input from a keyboard to produce output on a screen?īuxton wasn't alone in recognizing an eventual fusion of the two. It uses the same "hardware" for input and output of sound. The cup is both a microphone and a speaker.

He wondered why that same concept couldn't improve computer keyboards. When Bill Buxton worked at Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center in the early 1990s, he examined the classic children's homemade telephones: two cups connected by a taut string.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)